I am not very well versed in the “magical girlfriend” genre. I have nothing in particular against it, just never really found a gap in the armor of longevity each tentpole series wears. I’m sure that if I actually set down and read one of them, I could finish it in an afternoon or two, but then I’d feel all guilty for reading To-Love-Ru before even touching a page of Akira or Nausicaa and then… you see what I mean.

Either way, I picked up Chobits as something of a gateway point because it’s only 8 volumes long. CLAMP aren’t necessarily known for putting out super long runners (even Cardcaptor Sakura was significantly expanded on for the anime.) Despite this, trim tales like Magic Knight Rayearth and the aforementioned Cardcaptor Sakura stick with me for bearing a unique aesthetic (more on that later) and having a weirdly hot-blooded approach to love and human connection, reminiscent of something like Lyrical Nanoha. I’m not complaining; while it can get a little syrupy and saccharine for my taste, every CLAMP manga I’ve read stays firmly in a special kind of “warm and fuzzy” zone. I think that fascination with love, which arguably is a fascination with a person’s soul (at least in the CLAMP-verse), both works and comes about from the origins of CLAMP as a doujinshi circle.

You expected some high tier hair art, but it was me, an overused meme!

Yeah, that panel is from a CLAMP doujin. Either way, fan art has always fascinated me, especially really high-effort stuff like manga, fan games, homemade figures and the like. This is stuff that people can and do take as a full-time job, being done in free time just out of the drive to express something or passion for creating. As wary as I am of viewing the anime and manga continuum through too few lenses, I kind of see CLAMP’s origins as analogous to studio Gainax’s, being that they both broke into their respective industries not through working their ways up through the established order, but by making the kinds of work they wanted to see. Eventually, yeah, CLAMP manga would be serialized in major magazines like Nakayoshi and Weekly Young Magazine, and it’s less unheard of for manga artists to start off self-publishing when compared to anime studios, but CLAMP are still notable for being among the first doujinshi authors to later find major success with publishers. Certainly, they seem to give less leeway to editors than other mangaka who followed the same path.

Either way, all of their works I’ve read share an apparently visible through-line of themes and style. I think the most apparent of these is the trademark noodle people build all their characters tend to have. Regardless of their in universe heights, a lot of CLAMP’s characters have these really lanky builds that make them seem tall and graceful. Any child character will, guaranteed, be proto-moe as fuck, with huge eyes that are drawn with a more dynamic sparkle than the more simplistically adorable puni-moe look, or the “bug-eyed” Key style, that dominated the later 2000’s. Adults (and even teenagers in series like Cardcaptor Sakura) have much more balanced faces, with a pretty apparent triangular shape, kind of reminiscent of Yoshiaki Kawajiri’s character designs. You’ll notice that there’s usually at least one character with insanely detailed, very long hair that seems like a pain to draw. (Is D from Vampire Hunter D Bloodlust secretly a CLAMP character?)

Without even getting into the ways the stories will dress up the excuses for including cute and well designed costumes, we can see some clear author appeal here. I kind of hinted at it before, but a lot of CLAMP’s trademark design style wouldn’t feel out of place in a gothic action/horror piece like Vampire Hunter D. I haven’t read xxxHolic yet, but it seems like that’s the closest to that style CLAMP really gets. Most of their output is either shoujo (like Cardcaptor Sakura, Magic Knight Rayearth, Kobato) or else really sweet seinen romance (Chobits, for example.) Oh yeah, this post was originally supposed to be about Chobits, huh?

So the first thing that instantly grabbed me about Chobits was how… not-CLAMP it looks. The main character, Hideki, really looks more like any other harem lead than a CLAMP pretty boy, and that makes sense considering how Chobits is billed at the start. The first couple chapters consist of meeting his landlady, his teacher and his slightly younger co-worker. If you’re not savvy enough to the harem genre then this just reads as worldbuilding, but to those of us who’ve played the Keys and read the Nisekois, this is evoking something pretty familiar. All three characters have this semi-flirtatious rapport with Hideki, who at least acts oblivious to it all despite his clear search for a relationship. Over the course of the show we will see that a lot of these interactions come about as a result of different psychological hang-ups rather than genuine attraction. We’ll get back to that later, because none of it matters right now. At the end of the first chapter we meet obvious winner Chii, the robot girl- sorry, Persocom, thrown out in the trash.

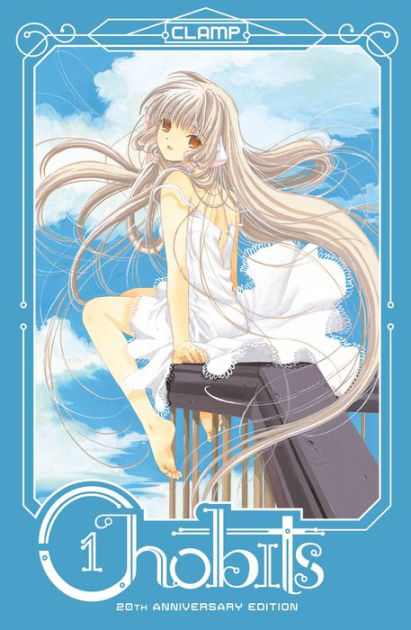

Chii’s aesthetic persona is what pulled me in, big-time, before I even cracked the book’s spine. I kind of alluded to it before, but while I’m not too experienced in the magical girlfriend genre as such, I have a real affection for turn-of-the-century dating sims like Yu-No and the Key works Air, Kanon, and Clannad. Not necessarily that I’ve played any of them to completion, but the late spring/early summer liminal, breezy and nostalgic atmosphere they’re drenched in just breaks me down to tears. It’s some combination of the really washed out ground and blue sky with that damn music- you know, the stuff that sounds like a hold tone? I’d almost call this aesthetic something like “unconstructed vaporwave,” and it hits me more in its sincerity than the inherently ironic vaporwave ever could. I’m getting off on a tangent. My point is that from the cover of volume one, Chobits establishes itself as sort of the manga equivalent to those old games, by way of some of the most auteur mangaka working today.

When I mentioned long-haired characters in CLAMP works before, they usually take the role of a mentor or a less physically active participant in the story, and while the individual strands of hair look stunning in their detail, I couldn’t help but feel like something was always missing from, say, the prim and poised portrait of Nadeshiko from Cardcaptor Sakura. That something is dynamic movement, something more than straight lines falling over each other. Just looking at the still image above you can just see Chii’s locks drifting and curling in the breeze, and being pulled by the inertia from her head tilt. You wouldn’t usually think to imply movement this much to sell a non-action manga, right? Especially not when you’re depicting a robot girl. This organic focus is very well considered, given that a central theme of Chobits is what it means to be human.

In the story proper, Chii is something else entirely. The fleetingness inherent to both to the aesthetic portrayed by the cover image and aesthetic personas in general is tied down and codified into a distinct character. Not the most unique one, mind; at the start, her personality is basically being innocent to the point of stupidity. I think some people would call it naivety, but I’ll be a little meaner since the point is that she grows from that to being a fully-realized, or at least realizable, love interest for Hideki. She goes from a human-shaped shell to project affections onto, a mirror to the beholder, to a person dedicated both to proving that she can love and to loving beyond the need to prove she can. And despite that change in her personality, Chii never feels any need to surrender the ethereal, angelic aesthetic persona we were introduced to. She still wears cute, well designed outfits, and her hair long, because that’s what CLAMP do.

I’m someone who has, at various times in my life, chased an unclear aesthetic persona for myself, told myself it was unattainable, and gave up to become a “real person.” Something that analyzing media has taught me is that aesthetic personas are just as much about the persona as they are the aesthetic; that is to say, finding one’s own aesthetic persona should come as a result of wanting to express something specific in how you present yourself, and not simply wanting to have an aesthetic to latch onto. In other words, I had the same journey as Chii, or about as similar as a human can have. I didn’t start out as a blank slate, but I sure wanted to be one for the sake of human connection, which of course backfired when people asked me why I liked them. There was no answer because I didn’t, not really, I usually just liked that they liked me. Looking back it’s one of those things I can’t believe I ever wanted to be, and I still feel almost guilty for having my own ambitions, dreams, and self, though not guilty enough to stop. Much like the Persocoms, my existence is a fact of this world, so I might as well exist to the fullest.

It’s not all so personal as that, though. In the world of sci-fi about robots, there are more explorations of this idea than you can shake a stick at. Hell, Ghost In The Shell even gets a shout-out in Chobits. That’s not for no good reason; the idea of AI being on par with, or surpassing, human intelligence can be explored in a multitude of different ways and is usually pretty interesting. Chobits seems to take the stance that being a complete human means being able to love, and being able to love understanding how your well being affects the well being of the people you care about. There really is no such thing as a perfect “loving sacrifice” in the book’s philosophy. For the sacrifice to be meaningful would mean burdening oneself, and to not make a sacrifice for a loved one would be pretty apparently selfish.

There’s a perfect example in Hiroyasu’s backstory, where his Persocom wife, despite being in the process of losing her mental faculties (as happens to outdated Persocoms) sacrificed herself for him to save him from a car. It’s heavily implied that Hiroyasu took this as a sign of her loving personality resurfacing after being buried through cloudy lenses of age, but I think it shows her base programmed function, her instinct, coming back. You see, Hiroyasu originally purchased his Persocom to help with “math and accounting” for his business. This mathematic specialty, to me, implies that, even in a state where cosmetics like the personality and memory are falling apart, she still has the power and right type of processing to weigh the risks and benefits of sacrificing herself for her husband to keep living. Regardless of this very logical approach to thinking about things, she is still remembered as a complete person by Hiroyasu, and presented as such by the story, because she didn’t throw her life away to give it some sort of purpose, she did it to save someone she cared about from being injured in the moment and from having to see her mental state degrade further.

Compare this to a flesh and blood human, Yumi. She’s similar to the aforementioned Persocom in a number of ways, but throughout the series her contempt for the artificial life forms manifests itself in a variety of ways, to the point that it almost becomes a moe trait. As the story progresses we see that her prejudice is based on an inferiority complex she developed to humanoid Persocoms. Yumi doesn’t have anything against the Persocoms as machines, really, but in that they’re stepping outside of that role and serving as replacements for human-to-human interactions. Her flirtatious behavior towards Hideki, which readers as genre-savvy as CLAMP are would read as “harem genre gonna harem genre,” are really an attempt to throw herself between Hideki and Chii, the human object of her affections and the machine she sees as a threat to his future. You might be seeing some parallels here, and they’re only exemplified when we later learn that Hiroyasu’s Persocom was also named Yumi (though that narrative choice was in the service of a different reveal, namely why Hiroyasu declined human Yumi’s advances in the time before the story started. You see why I didn’t mention Persocom Yumi’s name until just now? Moving on.)

The irony with these two characters is that the human who thinks humans are “running away” to Persocoms, machines that can never be people, is less of a complete person than one of the first Persocoms to marry a human. You can draw all sorts of real-life parallels to the divide between Persocoms and humans in the story, but unlike with a lot of speculative fiction I’ve read, I don’t think you necessarily need to in order to get something out of it. Most stories of this type, about AI becoming “just like humans,” wind up at the robot faction and the human faction coming to a conflict in a way that obviously is supposed to parallel some big issue from the time going back to, like, the Industrial Revolution. Anyone who’s flipped through a high school lit textbook has probably read a short story in that vein, and while researching what they meant in historical context makes them great teaching tools, I don’t think reading the same plot in a different cultural context necessarily makes a good story. This is where CLAMP’s history as trope-aware otaku comes in. They’ve likely overdosed on that type of genre fiction as much as I or anyone else following their work, has. In all the panels of Chii’s gorgeous, painstakingly-lined hair is a desire to impress the aesthetic of a cute robot girl onto the audience, and then hit them with the realities of sharing a world with these angelically beautiful fascinators who, nonetheless, have the lifespan of a personal computer.

Chobits is the kind of story that could only really hit me this way in manga. What I was expecting to be a fun, aesthetically driven story was that and so much more, by commenting on the very nature of the aesthetic persona. It’s an uncompromising artistic work, in the sense of someone who lives uncompromisingly. They don’t do things to hurt people not because people tell them not to, but because they don’t want to hurt people. Chobits isn’t uncompromising in the sense that its characters run through spirit-breaking gauntlets, but in that its an expression of something CLAMP very clearly are all about. It’s hedonist in the philosophical sense, that the creators made no bones about their author appeal, their love for magical girlfriend tropes, character and costume design, stories about what it means to love, and the many other CLAMP-isms Chobits bears on its sleeve. Similarly to Blame!, and another manga series I hope to talk about soon, it brings me up to speed with what artistic expression even means beyond lexically codifying what each shot or panel of a work communicates about the story or themes; the communication of a mood. The truly subjective, the stuff you gotta feel, the reason I write a blog in the first place. Goddamn. Chobits is indeed, pretty cool.

Thank you for reading my blog post, and I hope you stick around for more to come. Till next time!